“We must exterminate all men who have taken arms against the Republic

and strike down their fathers, their wives, their sisters and their children.

The Vendée must become a national cemetery.”

– General Turreau

The French Revolution is generally accepted as covering the period 1789 to 1799, ending with Napoleon’s coup d’état and the dissolution of the Directory. Prior to the formation of the Directory government France was ruled by the National Convention headed by Robespierre. This period, aptly known as the Terror, lasted from September 1793 to July 1794.

For Western France, in the region of the Vendée, the Terror was accompanied by bloody and religious civil war including a period of mass killings that some French historians have recently come to denounce as a genocide and which led to the decimation of a third of the inhabitants in the Vendée.

In the Western town of Nantes the representative of the National Convention, Jean-Baptiste Carrier, was responsible for atrocities and massacres that defy imagination.

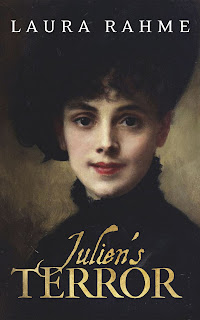

In my latest novel, I was interested in portraying a female perspective for this turbulent period.

Origins of the Conflict

The inhabitants of Brittany and of the newly named region of Vendée (comprising parts of Brittany, Poitou and Anjou regions) were never in favor of the guillotining of their king, Louis XVI, on 21 January 1793. They were staunch royalists and deeply Catholic. The execution of King Louis was not well received.

To compound the people’s outrage, the new Republic had not only nationalized church property, but it also outlawed all priests who refused to forsake their oath on the Holy Bible. According to these new laws, priests now had to swear upon the Constitution. Those who resisted were labelled ‘refractory’ and banished from preaching. There were persecutions involving both priests and nuns. In worst cases such priests were hunted to death or murdered en masse, as happened in Nantes in December 1793 when hundreds of refractory priests were tied up, locked into a barge and drowned in the Loire River.

Already unsettled, the Vendée peasants rose in arms against the Republic when in February 1793, the National Convention made a call for the conscription of 300000 unmarried men, from the age of 18 to 40 years.

The people of the Vendée had already witnessed great injustices toward their beloved priests, whom they hid, but this new conscription law was the tipping point because it would have left thousands of peasants unable to fend for their families. Meanwhile they would be forced to enlist in support of a Republic they had come to see as tyrannical.

Determined to oppose the Republic, these men, often illiterate and attached to their land, elected nobles and landlords—local men whom they held in high esteem—to lead and train them in battle. The Great Vendéan Army was born.

Initially this Great Army won many victories against the soldiers of the Republic, but from December 1793, its luck began to turn. From January to July 1794, Paris sent a giant army to sweep across the Vendée. Its orders were clear: annihilation with no quarters.

The Infernal Columns

The army possessed twenty columns led by several Republican generals. Some, like those commanded by General Grignon, were more cruel than others. These columns became known as the ‘infernal columns’ for the very hell they spawned.

The living defend their dead. War of the Vendée.

Georges Clairin, 19th century

The words pronounced by General François Joseph Westermann are powerful illustrations of the atrocities that followed:

“There is no more Vendée. I have trampled the children to death with our horses, I have massacred the women, and they are no longer able to give birth to any brigands. I am not guilty of taking a single prisoner, I have exterminated them all… The roads are covered with corpses. There are so many of them at several places they form pyramids. The firing squads work incessantly… Brigands arrive who pretend that they will surrender as prisoners… but we are not taking any. One would be forced to feed them with the bread of liberty, but compassion is not a revolutionary virtue.”

Writing the French Revolution

My female character is barely nine when she loses her parents to Carrier’s butchery. She is reunited with relatives in war-torn Vendée, staying with them first in Montaigu, La Guyonnière and then later in Les Epesses—all communes that were swept by the infernal columns.

The Underground and the Hidden Places of the Vendée

As François Pagès describes in Secret History of the French revolution—the soldiers of the Catholic royalist army ceaselessly disappeared and then re-appeared to fight. The underground, the woods, the stones and the marshes in the West would conceal and then suddenly release hordes of former valets, brigands, priests, ex-nobles, and peasants. They were everywhere and yet they remained unseen.

In his final novel, Quatre-Vingt Treize, Victor Hugo wrote of his father’s experience in the war against Breton royalists. He too mentions the forests that sheltered thousands of peasants in Brittany:

“The peasant had two points on which he leaned: the field which nourished him, the wood which concealed him.”

“There were wells, round and narrow, masked by coverings of stones and branches, the interior at first vertical, then horizontal, spreading out underground like funnels, and ending in dark chambers. [ ] The caves of Egypt held dead men, the caves of Brittany were filled with the living.”

“The subsoil of every forest was a sort of mad repose, pierced and traversed in all directions by a secret highway of minds, cells, and galleries. Each one of these blind cells could shelter five or six men.”

In Les Epesses, my female character follows her great-uncle, a giant Breton man who walks everywhere with his large wooden staff, and seems to know all the secrets of the underground. He hides his family in an underground cavern where they remain for months.

As the infernal columns advance in the Vendée countryside, my character witnesses horrors beyond her years. Later she will hide in the secret Gralas forest, south of Nantes, and meet one of the most courageous men to lead the Vendée rebellion – General François Athanase de Charette de la Contrie (Charette). In Gralas, she will also discover the strong, independent women who fought to death alongside Charette, and one of these women will change her life forever.

"Liberty, Equality, Fraternity or Death"

- the original motto of the French Republic

Further Reading:

1. Histoire secrète de la Révolution française depuis la convocation des notables jusqu' a la

prise de l'ile de Malthe..., François Pagès, 1798.

2. Quatrevingt-treize, Victor Hugo, 1874.

3. Souterrains de Vendée, Laurent et Jérôme Triolet, Editions Ouest-France, 2013.

4. Colonnes Infernales - Wikipedia

5. A French Genocide: The Vendée, Reynald Secher, University of Notre Dame Press, 2003.