The alluring Gong Li in Tang Dynasty film,

Curse of the Golden Flower

Nothing quite spells mystery like a glimpse into

China’s forbidden palaces, centuries ago. Stepping back in time over 600 years ago, to the Ming Dynasty, one wonders about the women who dwelt in the palaces of Beijing and Nanjing. Unlike the daring women of the Tang Dynasty (618-907 AD) who lived in Chang'an Palace opulence and shied not from revealing skin or cleavage, Ming court women were more demure.

During the early Ming Dynasty the dragon throne, seat of the emperor, lay in the palace in Nanjing, a cosmopolitan city then known as Yingtian.

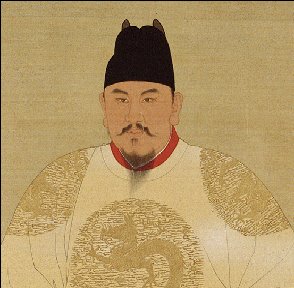

Emperor Hongwu - Zhu Yuanzhang

Founder of the Ming Dynasty

Emperor Hongwu, the first Ming emperor had just driven out the Mongols from the Middle Kingdom. Like many Chinese emperors before him, and much like the former Mongol rulers who had ruled China from Dadu (modern day Beijing), Emperor Hongwu owned a Royal Chamber or harem where lived, or so he hoped anyway, the most gorgeous creatures in the country and beyond.

Who were these women? Where did they come from? Standards of beauty vary enormously between historical periods and cultures. What were the primary physical attributes that rendered a woman attractive in Ming China? And were these women happy?

To answer these questions, we travel back in time to the Yingtian Palace. Here, in the Inner Palace, only the emperor, his eunuchs and the court ladies or maids can usually enter. But today for this exclusive interview with a Ming concubine, we have been permitted entry by a corrupt eunuch. We will sit under a pavilion in the Imperial Gardens and we will ask the delicate Zhou Mai, a fifth-ranking concubine, to tell us a little bit about herself, her beauty routine and what her experience has been so far living in the palace.

Greetings Zhou Mai. Where do you come from?

I was born in Korea. My country pays tribute to the Hongwu Emperor. This is a demonstration of my people's loyalty as vassals to the Middle Kingdom. In exchange, Korea is offered protection from pirates. It can also trade with the people of the Middle Kingdom.

Is it true that you were sent to the Middle Kingdom as a gift?

Yes. Last year, the Hongwu emperor asked that my country pay tribute by sending him one hundred virgins. I was one of the girls chosen to be his concubine.

How old are you?

I am thirteen.

Did you want to be selected?

It is an honour to serve in Emperor Hongwu's Royal Chamber. But...I miss my family. My parents were very upset to see me go.

Where do you live now?

I live here, in Yingtian palace. We girls sleep in the Royal Chamber quarters. We cannot go outside the palace.

What is your palace title?

Here, I am called Zhou Guiren. Guiren is an honorific title for fifth-ranking concubines like me. I want to be a Guifei. This is a first-ranking concubine. I have much to learn. I can only become Guifei if the emperor is pleased with me or if I bear him a son.

What were the reasons you think you were selected?

I was told my skin was as pure as jade and white as glistening snow. In the Middle Kingdom and Korea, fair skin is very important. Also my breasts are not too big as I have bound them tight from an early age with strips of cloth. Having big breasts is seen as salacious. I think also, I have a lithe waist and have always been encouraged to shuffle graciously with tiny steps. I am well-spoken and have a good voice.

I noticed that you do not have bound feet. Do not the women of the Middle Kingdom bind their feet?

We Koreans do not bind our feet.

Yes, is increasing in the Middle Kingdom today. It is called "lotus feet".

So some women in the Middle Kingdom have bound feet and some do not?

The Mongols tried to outlaw the custom. They have since been pushed out, back to the North. Emperor Hongwu, is against all Mongol practices. Now is becoming popular again all over The Middle Kingdom.

But there are still exceptions. Even Emperor Hongwu's consort, Empress Ma does not have bound feet. She is from Mongol stock. She even rides horses.

Why do you think men of the Middle Kingdom like bound feet?

Any man with a good reputation prefers his woman to stay in the home so she cannot invite illicit affairs. A woman with bound feet cannot easily walk. So she is less likely to leave her husband if she wanted to.

Also only country women who work outside in the fields need use of their big feet. So for a man to be seen as wealthy, it is best that his woman has lotus feet.

Do you wish you had bound feet?

(frowns) Yes...and also...no.

Why?

Lotus feet are seen by some women as more precious than a beautiful face. They say men are excited by lotus feet. They play games with them in bed. But then I know that lotus feet cause a lot of pain. In the Royal Chamber, girls with bound feet need help to squat for toileting. They are dependent on their chamber maids. I often hear concubines complain about pain.

What do you do with your time, Zhou Guiren?

We do many things. We like to read books. They are not illicit tales from the streets, they are mostly virtuous books written by Empress Ma, Hongwu's consort. Also the educated ladies from Suzhou in the south come to visit us often. They are very talented. They teach us songs and music. They teach the younger girls to read. I like to embroider animals on silk. I am getting better at silk embroidery.

Do you go outside your chamber?

Yes, when it is not too hot. We ask the eunuchs to bring parasols for us and we play in the Inner Palace's gardens. We play behind the rocks and sing songs. But we cannot go outside the palace. On special occasions, some Guifeis will travel on sedan-chairs and accompany the emperor to visit the other palaces where the princesses and princes live.

You mentioned illicit tales before. What are those?

They are road-side tales told by ambulant storytellers in the cities and the country. I am told they can be crude and not virtuous. Some tales have been made into bound books by the publishers of Fujian province in the south. But we are not permitted to read these. We are only allowed virtuous literature. Women should be modest, chaste and Tend to the Gentlemen. This is our highest calling.

Long silk pleated skirt, blue is usually a colour no commoner can wear

The ribbon tied coat is a little passe, Zhou Mai preferring buttons

What are you wearing Mai?

(stands) On my feet, I have slippers with peony pattern embroidery. I am wearing a long white silk pleated skirt. Pleated skirts are the latest fashion in the palace. On top of this, I have a silk peach waist coat with porcelain buttons. Buttons are very good to have.

I like being a concubine because we have beautiful silk clothes. Country people can only afford cotton or hemp.

Did you do your hair yourself?

(smiles) My chamber maid helped me with this double bun. She picked blue flowers from the imperial garden and pinned them to the sides above my temples. One of the princesses gave me a gift of this cobalt tasseled pin and I have pushed it into my bun. This type of pin is only for girls who have reached menstruation.

Ming Dynasty Hair ornaments

Tasseled pins adorn double buns

Tell me more about your makeup and beauty routine, Mai.

It is important to keep the skin white and so we use powder from crushed shells. After covering my face in powder, I draw-in my eyebrows into black crescent shapes and spread a vermillion-tinged pomade on my cheeks to bring them to life.

I use a vermilion lip balm to draw a cherry-shaped pout in the centre of my lips. It should not go out too much, only three quarters of the lip should be covered.

On my nails, I have a red nail tint made of egg-whites, beeswax, balsamic dye and Arabic gum. Last month, my nails were tinted in black but I decided to change today. I wear a scented pouch around my waist to give off pleasant smells wherever I walk. (touches earrings) These jade earrings are a gift from the emperor. (smiles)

All this is what men find beautiful.

The cherry-shaped pout in latest vermilion

You mentioned eunuchs before, what are those?

They are men who have been castrated. They cannot have children. They are the only men we see in the palace aside from the emperor.

What do you think of eunuchs?

Some are not to be trusted. But others are very helpful. It depends. They are from all over the country including the south in Yunnan province. Others come from as far as Annam, Korea and Manchuria. There are some eunuchs who never wanted to be eunuchs but they had no choice because they were made prisoner by the emperor's men and taken by force, like the Mongol eunuchs for example.

What is the role of eunuchs in the palace?

They work hard in the palace. They do everything for us. They bring toilet paper, empty chamber pots, call onto female physicians and they organise our foot warmers, parasols and sedan-chairs. They will bring us to the emperor's night chamber whenever we are selected to spend the night with him. They do everything in the palace but they cannot read.

Why can they not read?

(whispers) The Hongwu Emperor has forbidden that eunuchs learn how to read. He believes they should not be trusted with important documents.

What about the Royal Chamber...do you girls trust the eunuchs?

(hesitates) Well...I will tell you something that the emperor does not know...yet. Some of the concubines have eunuch lovers. They meet them in secret...

Why do you think the concubines seek a eunuch lover?

I don't know. Because...they are lonely maybe. They miss their family...but eunuchs are always here for them. Also some of the concubines can seek the attention of eunuchs when they are sad or lonely. You see, even if a concubine has children, these are taken away from them as soon as they are born and sent to the nursery in the Eastern side of the palace.

Do you think you will ever return to your homeland?

Maybe. I think it is not likely. When concubines are old, around thirty years, they are sent to do laundry or become maids. They also cannot remarry with a man from the Middle Kingdom, only with a foreigner. Maybe I will die an old maid. But I am still lucky. I could be on a farm working hard on the land with not much food to eat. The emperor knows everything about famines. You see, when he was a young boy he lost most of his family in the Anhui famine. (smiles) So I am lucky living here in the palace.

Thank you, honourable Mai Guiren, for your time. It has been a pleasure.

May the path you walk on be sprinkled with the most fragrant flower blossoms and may you live a long life.

An erotic embossment on a brick - Ming Dynasty (1368-1644)

Courtesy of the Chinese Sex Museum in Xi'an

Published in AvaxNews.com

Did you like this post?

A new historical novel, The Ming Storytellers crafts a mysterious tale of imperial concubines and eunuchs set against the political intrigue and obsessions lurking in the palaces of Beijing and Nanjing. Set in the early Ming Dynasty, The Ming Storytellers brings to the fore the lives of imperial concubines during this period. It is available internationally from Amazon (Paperback and Kindle Editions), Barnes & Noble NOOK and Apple's iBookstore.