Julien's Terror features various facets of the psychological thriller listed by Mecholsky1 including, apparent paranormal danger, a form of prolonged psychological torture, psychological trauma / memory losses and past traumas that revisit in the form of a new danger.

Julien, my main character, experiences a dread towards his wife, Marguerite which has as its origin: family trauma; the internalisation of a misogynistic mentality that would have been common in the 19th century; the internalisation of his own father's jealous paranoia towards Julien's mother; and finally the suppression of his own inner fears which rebound forcibly, manifesting into a terror. This is revealed during his final visit to fortune teller Marie Anne Lenormand, where Julien makes a powerful revelation about a crucial passage in his life.

The only person in the novel who appears fearless in the novel is Marguerite, adding to the aura of mystery and potency around her.

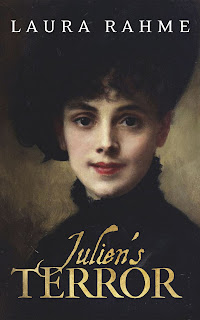

A young Marguerite Lafolye

Painting by Gustave Jean Jacquet (1846-1909)

For all his knowledge, engineering aptitude and cerebral prowess, Julien cannot decipher his own wife. Marguerite appears as an unknown entity. Mid-way into the novel, he considers her a liar, perhaps even a traitor.

According to Mecholsky, this fear is key to the psychological thriller. He claims that this dread, that dangerous secrets lie beneath once-safe sectors of life is in fact an anxiety about the modern age and its implication. Despite living in an Age of Reason which had presumably enabled the French Revolution, despite having been rigorously schooled by the Ponts et Chausses, the Cartesian Julien is confronted with the limits of his knowledge. He knows nothing about Marguerite. Before him, is an unknowable being, one who reflects the unknowable mind in each and every one of us.

Aptly set in the French Revolution, Julien's Terror illustrates this modern dynamic that Mecholsky describes as having given birth to the psychological thriller - a modern anxiety (about the nature of the mind and the Self) existing through the Enlightenment struggle to subjugate myth and superstition by way of science and rationality. Marguerite is a Catholic royalist. Worse, she is of Breton descent. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the Bretons were considered not only filthy by the French, but also savage and backwards. Meanwhile, their 'blind' adherence to religion was seen as evidence of their superstitious minds. Julien's domination and abuse of Marguerite is a metaphor for this symbolic subjugation of the rational over superstition and myth.

As modern anxiety would have it, Julien does not fare better through his actions - his anxiety only accrues and the enigma of Marguerite appears all the more horrifying. It is only when Julien takes Marie Anne Lenormand's advice and considers the supernatural as a potential explanation for what is happening - at the cost of his cherished logic, only when he concedes that there may be forces he knows nothing about, and then pragmatically undertakes to confront these occult forces, can he achieve a solution.

Marie Anne Lenormand reading

In its resolution, however, Julien's Terror presents two opposing explanations for the reader that can be listed here briefly to avoid spoilers. The first explanation is grounded in rationalism, informed by a conversation with the physician Franz Anton Mesmer. Mesmer proposes a valid psychological theory, albeit one that had not been fully developed at the time, and which was only starting to be known in limited scientific circles, due to the rising cases observed and reported.

The second explanation is supernatural. It confirms Marguerite's innate belief that she can see and converse with the dead. It suggests that there is something real about the myths in Breton folklore - they are not mere superstition. This explanation also implies that Marguerite, by way of a certain unique and harrowing childhood experience, now finds herself between two worlds - she lies in-between - and as such, she can channel the dead.

Les Lavendieres de la Nuit - Breton Folklore painting by

Jean Edouard Yan Dargent (1824-1899)

At the conclusion of the novel, Julien rationalises what he has seen, to himself. He is never truly convinced about one explanation over the other, but he now understands that there is something strong and worthy of esteem in Marguerite. He is also made aware of his own past failings - though that is not to say that he has overcome them (an important point, if one is to understand his last vision in the Temple prison). He comes to cherish, admire and love Marguerite all the more. An ending like this was necessary to reconcile the couple after much conflict and to achieve a satisfying character arc for Julien.

Despite Julien's own reckoning, I don't want underplay the tone of uncertainty that the final chapter creates - this fine line between the rational and the paranormal interpretations is the hallmark of the psychological thriller. We are not meant to know for certain. Some anxiety remains.

The horror that Julien's Terror illustrates is both a facet of the period during which it is set (the French Revolution/ the Terror / the Vendée wars) and the repercussions this period had on the French population.

Mecholsky indicates that the French revolution was a logical cultural goal of the Enlightenment, yet it resulted in horrific terror and murder, casting a pall over rationalism. Julien embodies this contradiction perfectly. He is both the most logically-minded character and the character that undergoes the most destructive and potentially sociopathic psychosis. Incidentally this is the reason the novel is named Julien's Terror.

Just as it opposes rationalism to superstition, Julien's Terror also highlights the ever present conflict between those French who embraced the Republic and were loyal to its tenets, and those French who pined for the Ancien Regime and espoused the royalist cause. This opposition is embodied by Julien and his wife Marguerite.

Julien is an upcoming bourgeois who has thrived in the new Republican order and accepted the Napoleonic age. He considers Napoleon his benefactor and the benefactor of France. Marguerite is a staunch royalist with a great disdain for the 'Corsican upstart' who has come to rule post-revolutionary France.

When I conceived a marriage between two unlike souls, I was partly cautious about its probability. I decided, among other character motivations, to employ a 'marriage of convenience' disclaimer - Julien marries the first woman offered to him to avoid serving in Napoleon's army so that he can instead become the engineer he had always dreamed of becoming. With this mindset, he spends no time evaluating her personality, background or values. By way of this disclaimer, I hoped no one would question such an unmatched pair. Still, I wondered how likely an alliance of this nature could have been. Could a republican at soul marry a royalist?

I had no idea that this unlikely combination was in fact common. So common, that it existed in none other than author Victor Hugo's family2. The similarity struck me and I simply have to share it here.

Like Marguerite, Victor Hugo's mother was from Nantes. Like Marguerite, Sophie Hugo née Trébuchet, was from a royalist Breton family. And like Marguerite, Sophie did not share her husband's Napoleonic sentiments. Madame Hugo went so far as to shelter those who plotted against Napoleon's life. Meanwhile, Hugo's father, Joseph Léopold Sigisbert Hugo distinguished himself as a soldier in Napoleon's army, rising to a high position, notably at the battle of Marengo in 1800, acquiring the Legion of Honour in 1804. He also fought against guerillas in Spain from 1808 to 1810 a period during which the young Victor Hugo became acquainted with the Spanish language and learned to love the country.

Sadly, and unlike Marguerite and Julien, the Hugo couple's differences could not be resolved.

A final word about Julien's Terror. Mecholsky explains that novels like the psychological thriller and its early Gothic form have helped us disguise sources of anxiety, throughout the history of western culture since the 18th century. Quoting Fiedler, Mecholsky alludes to one of the tensions that such novels help us deal with: "a fear that in destroying the old ego-ideals of Church and State, the West has opened a way for the inruption of darkness..." I think this is perfect. You see, as a psychological thriller, Julien's Terror happens to be set during and soon after the French revolution, that is to say a period where the power of the Monarchy and Church were toppled, leading perhaps to much anxiety and guilt... Here then, Julien's Terror provides a coping mechanism for a fear that has presumably surged during the very period in which the novel is set.

Sources:

1. Kristopher Mecholsky, The Psychological Thriller, http://www.academia.edu/17484925/The_Psychological_Thriller_An_Overview, Accessed on 12 June, 2017.

2. Albert.W. Halsall, Victor Hugo and the Romantic Drama, University of Toronto Press, 1998.

Sources:

1. Kristopher Mecholsky, The Psychological Thriller, http://www.academia.edu/17484925/The_Psychological_Thriller_An_Overview, Accessed on 12 June, 2017.

2. Albert.W. Halsall, Victor Hugo and the Romantic Drama, University of Toronto Press, 1998.